Back in 2009, it seemed like Obama might champion a nationwide high-speed rail system or a sophisticated new power grid. Ultimately, his administration took a largely piecemeal approach to advancing a progressive urban vision. TIGER encouraged cities like Hartford, Conn.; Akron, Ohio; and Sacramento, Calif., to restore disused train stations, implement bike sharing, and build light-rail or bus rapid transit lines, transforming the country one modest project at a time. “I think the TIGER program has been very successful,” says Shelley Poticha, a former Obama administration official who is now the director of urban solutions for the Natural Resources Defense Council. “It really prioritized investments in local communities and it has empowered [them] to actually use the funds and deliver the projects in a holistic way. It’s probably the only transportation program where the money goes directly to the city.”

Under the new administration, however, TIGER grants may well disappear. The 2018 budget released by the White House in May includes over $16 billion in cuts to the Department of Transportation, and in mid-July, the House passed a spending bill that would eliminate the program. Then, in late July, the Senate Appropriations Committee proposed setting TIGER’S funding at $550 million next year, an increase of $50 million. Will the program survive, or is it destined for a premature death?

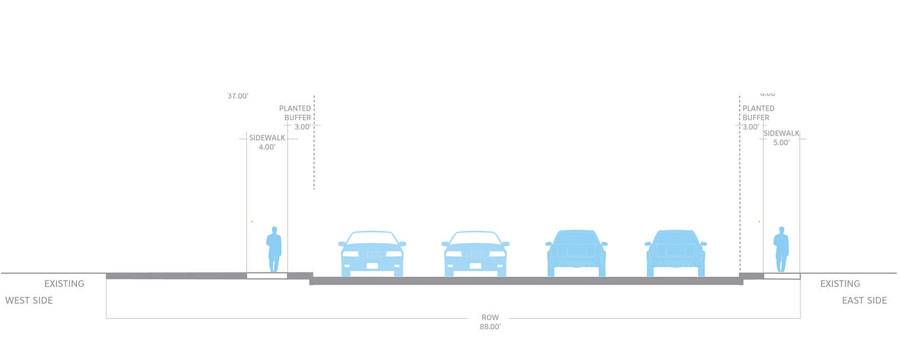

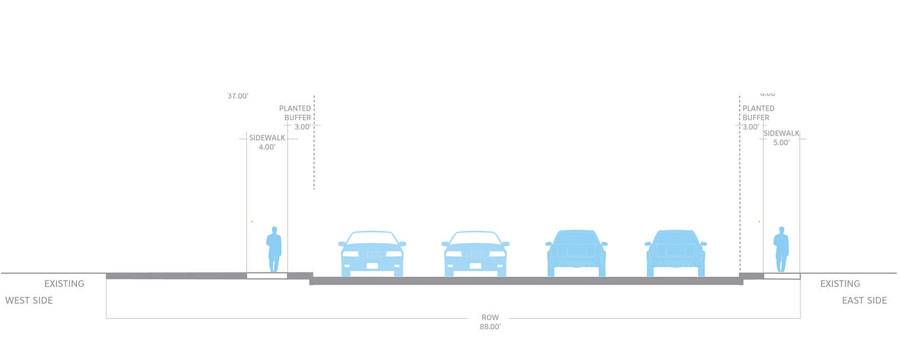

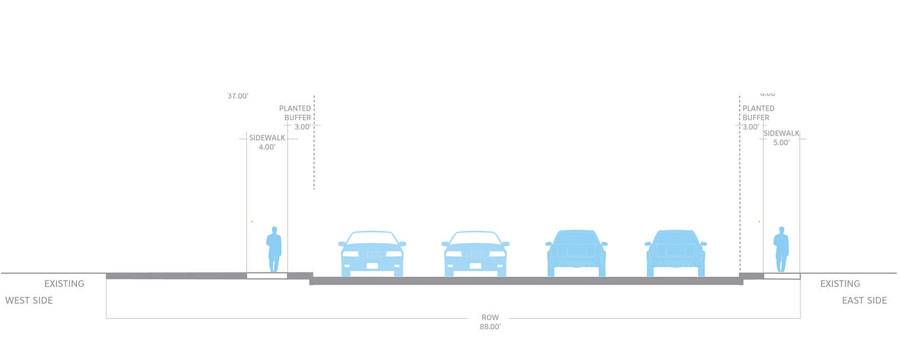

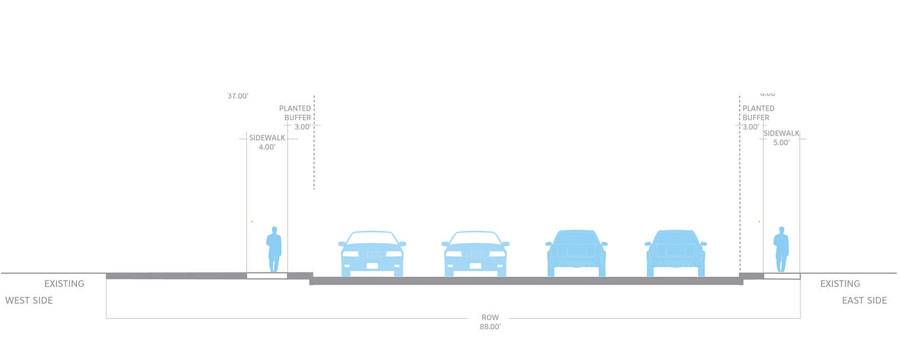

Vine Street today and after the redesign

Lexington’s Pedestrian Push

To discover what might be lost, I traveled to Lexington in late June to learn more about Town Branch Commons, which is exactly the kind of quirky, forward-looking project that the TIGER program encourages. During the urban renewal decades, Lexington managed to avoid having an interstate highway rammed through its center, and much of its historic Main Street remains intact. Downtown, a hulking Richardsonian courthouse is currently being remodeled into a visitors’ center (bourbon tours!) and the former slave market has been recast as the site of a weekly farmers market. The city’s dining and bar scene is enlivened by two colleges, the University of Kentucky and the tiny, oddly named Transylvania University that, founded in 1780, was the first college west of the Allegheny Mountains.

In 1958, demonstrating considerable foresight, Lexington created an urban growth boundary around the city, so there’s very little suburban sprawl. Leafy residential neighborhoods that ring the downtown quickly give way to horse farms. What’s conspicuously missing, however, is the sort of exalted bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure that has become the hallmark of the 21st-century city. Also MIA: the creek that was Lexington’s original raison d’être.

Which is how I found myself standing with Orff in the parking lot behind the 1976 Lexington Center, an oddly disjointed assemblage of glassy cylinders in front and corrugated concrete in the rear, which incorporates a hotel, shopping mall, convention center, and Rupp Arena, home to the University of Kentucky’s basketball team. The parking lot will eventually be transformed into Town Branch Park, a 10-acre privately funded green space with lawns, performance spaces, and a creek-inspired splash pad—a tantalizing destination for bikers and walkers along the new greenway.

Scape

A rendering of a waterpark near the convention center

Right now, the site is nothing more than a sheet of asphalt facing the sorry underside of the center. The stream runs under the blacktop. “Where you see the drains,” Orff says pointing to a line of sewer grates, “is the Town Branch culvert.” Beyond the edge of the parking lot, which is pretty much the downtown’s western limit, and beyond a metal highway barrier that gives way to an expanse of grass, the waterway itself reappears, a perfectly pleasant little stream.

Town Branch Commons is exactly the sort of undertaking for which Orff is building a reputation. The founder of Scape, and the director of Columbia University’s graduate Urban Design Program, Orff is at the forefront of a movement in which a deep understanding of the natural world informs the design of the manmade one. Scape won the project in a 2013 design competition sponsored by Lexington’s Downtown Development Authority, and construction is scheduled to begin later this year.

The Idea of a City on the Water

About two decades ago, a local architect named Van Meter Pettit, AIA, figured out exactly what Town Branch meant to Lexington. His family happened to own a McKim, Mead & White building downtown (now the 21C Hotel), whose basement required nonstop pumping and that clued him in to the creek’s existence. Familiar with the Delaware and Raritan canal towpath in central New Jersey and Austin, Texas’ Town Lake trails, he could envision the lost stream’s potential. In 1998, Pettit founded an organization called Town Branch Trail, with a mission to “connect the city with its world-famous countryside and reorient the cityscape to its founding along the creek.”

In 2010, Jim Gray, a local contractor, was elected mayor, and he set up a task force to update and improve the convention center area. According to planner Stanford Harvey, a principal at Lord Aeck Sargent and a long-standing participant in the project, the new mayor “saw a waste and an opportunity, that the city owned 46 acres right in the middle of downtown that was mostly surface parking lots.”

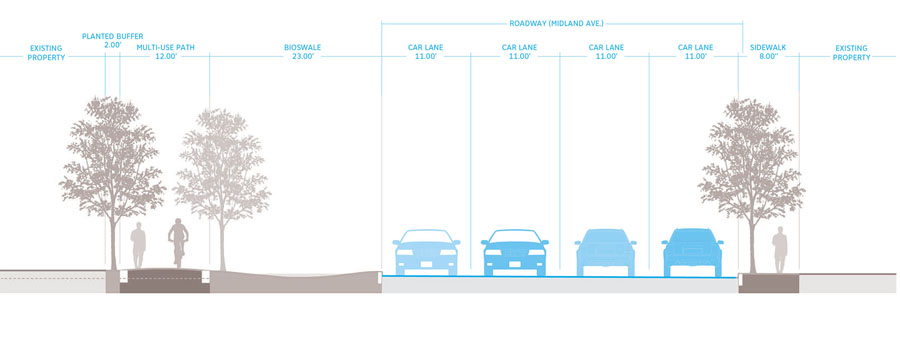

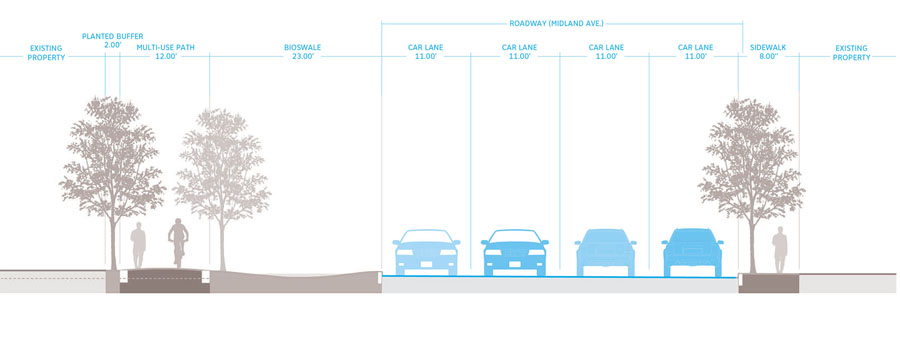

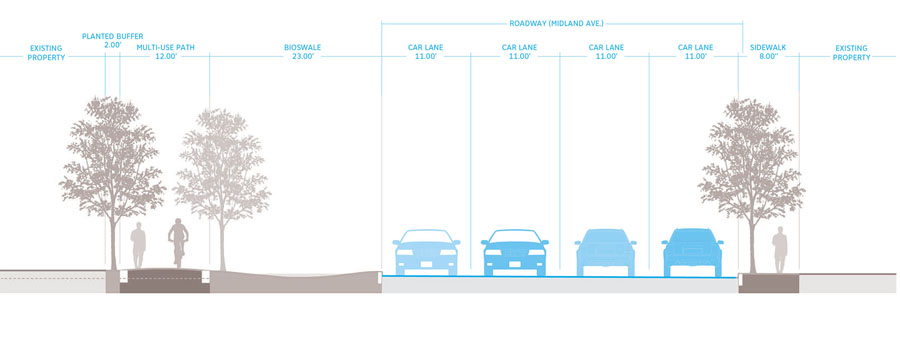

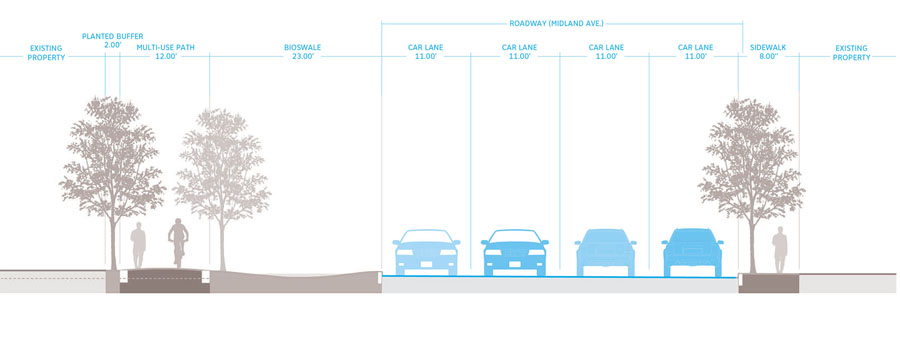

Midland Avenue now and after the redesign

The task force hired architect Gary Bates from Oslo, Norway–based Space Group. “Gary got it immediately to an extent that kind of amazed me,” Pettit recalls. “He made Town Branch the centerpiece of his schematic plans.”

As Harvey explains it: “I think there’s two things that resonated. One is this idea of a city on the water, the idea that they thought we somehow are going to bring water back.

“And the second thing is,” Harvey continues, “Lexington is pretty much defined by the horse farms, so this idea of a green ribbon coming through downtown that is somehow about the farms and what Lexington means … people really liked that idea too. Particularly if it’s a trail that connected out to those farms as well.”

“The arena project was shelved,” says Pettit, “but the Town Branch concept was promoted as a stand-alone design competition.”

In the ensuing proposals, most of the firms did the obvious thing, according to Gena Wirth, a design principal at Scape: They daylit the length of Town Branch through downtown, liberating it from its culvert, and made it into a riverwalk, like the one in San Antonio, even though Town Branch is a far less substantial waterway. Scape, on the other hand, immersed itself in the natural environment of the bluegrass region, in particular the way a porous limestone called karst has shaped the local economy and ecology. Apparently, the limestone nourishes the grass, thereby strengthening the bones of the horses that graze on it; it also infuses the bourbon for which the state is famous. And it causes water to behave in unusual ways, which influenced Orff’s design. In her 2016 book, Toward an Urban Ecology, she wrote: “Underground waterways travel through permeable limestone layers and surface into pools, disappear into sinks, and dramatically resurface where least expected. Rather than express Town Branch as a linear channel, the project aims to reveal a karst identity through a network of water windows, pools, pockets, fountains, and filter gardens that evoke and expose the underground stream.”

A diagram of the streetscape now and after the redesign

Scape’s idea is clever: Town Branch Commons will be a linear park squeezed into space created by narrowing the traffic lanes on Vine and repurposing some of downtown’s many surface parking lots. The park will be continuous, but the actual creek will not. Sometimes it will be evoked with pools, stormwater-cleansing filtration gardens, and a variety of other water features. The distinctive karst walls, made from diagonal slabs of stone, common in the surrounding countryside, will be a recurrent motif in the project, used as the inspiration for benches, barriers, and paving patterns.

The Department of Transportation, in awarding Town Branch Commons the grant, saw the project as a “multimodal greenway” and was especially swayed by the idea that the section it was funding would link to 20 additional miles of rural trails. The project’s overall budget, just shy of $40 million, also came from other federal sources, plus city and state transportation and environmental budgets. The two largest park areas are being paid for separately, by private donations. But it was the TIGER grant that made the project feel like a done deal, according to Harvey: “People were taken aback: They actually raised all of the money to do this. This is actually going to happen.”

Mayor Gray discusses Town Branch Commons the way his 1970s predecessor likely spoke of the convention center: “I’m saying it’s essential, essential in the competitive landscape today,” he told me. “Having a compelling, inviting, welcoming urban space through it is a big part of maintaining competitive advantage in an economic sense.”

Gray’s director of project management, Jonathan Hollinger, put it this way: “We see this as 21st-century infrastructure. What we’ve done over the last 50 years is built infrastructure for cars.” No matter how technology changes the city’s future needs, he argues, “I can say with great certainty that we’ll always be able to walk.”

Vine Street now and after the redesign

What Losing TIGER Would Mean

The revitalization of American cities that has occurred over the past decade can be attributed, in part, to the way the federal government has rewarded urban centers that took the needs of their walkers, bicyclists, and transit riders seriously. This hasn’t prevented the Trump administration from targeting TIGER grants in its budget. In theory, the Town Branch project should appeal to politicians on both sides of the aisle. In fact, Lexington officials rallied support for the TIGER grant from Sen. Mitch McConnell (R). When I recently spoke to Shaun Donovan, the former secretary of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, he emphasized that encouraging and funding innovation at a local level should be a bipartisan effort: “In some ways, it’s very consistent with the federalist view of the Republicans that the federal government ought to be a supporter of local communities rather than dictating to local communities.”

Although light on specifics, the Trump administration’s approach to infrastructure appears mainly to be about injecting money into big-ticket projects like highways and airports by privatizing them. There doesn’t seem to be a lot of interest in mass transit and other less carbon-intensive forms of transportation. As Poticha told me: “The message I’m getting from the Trump administration is that they’re only really interested in these big projects that private equity investors can see a return of investment on.”

In other words, this is not an administration that appears intent on embracing the kind of progressive urban thinking that is one of Orff’s strong suits. She describes her approach to incorporating the local ecology into built works as a “revival,” which she defines as “a creative, forward-looking act, not driven by nostalgia for the past.”

Indeed, much of our 21st-century infrastructure has been aimed at repairing the damage done by monumental 20th-century infrastructure. TIGER supports projects that accomplish these aims in a way that isn’t always photogenic or sexy, that may not have the appeal of a cathedral-like airport terminal or a soaring bridge. If Trump’s cuts to TIGER are included in the budget that Congress is slated to pass this fall, what will be lost is a program that prioritizes the layer upon layer of interlocking systems that are frequently unglamorous and boring, and sometimes, like that lost creek in Kentucky, entirely hidden from view.

Back in 2009, it seemed like Obama might champion a nationwide high-speed rail system or a sophisticated new power grid. Ultimately, his administration took a largely piecemeal approach to advancing a progressive urban vision. TIGER encouraged cities like Hartford, Conn.; Akron, Ohio; and Sacramento, Calif., to restore disused train stations, implement bike sharing, and build light-rail or bus rapid transit lines, transforming the country one modest project at a time. “I think the TIGER program has been very successful,” says Shelley Poticha, a former Obama administration official who is now the director of urban solutions for the Natural Resources Defense Council. “It really prioritized investments in local communities and it has empowered [them] to actually use the funds and deliver the projects in a holistic way. It’s probably the only transportation program where the money goes directly to the city.”

Under the new administration, however, TIGER grants may well disappear. The 2018 budget released by the White House in May includes over $16 billion in cuts to the Department of Transportation, and in mid-July, the House passed a spending bill that would eliminate the program. Then, in late July, the Senate Appropriations Committee proposed setting TIGER’S funding at $550 million next year, an increase of $50 million. Will the program survive, or is it destined for a premature death?

Vine Street today and after the redesign

Lexington’s Pedestrian Push

To discover what might be lost, I traveled to Lexington in late June to learn more about Town Branch Commons, which is exactly the kind of quirky, forward-looking project that the TIGER program encourages. During the urban renewal decades, Lexington managed to avoid having an interstate highway rammed through its center, and much of its historic Main Street remains intact. Downtown, a hulking Richardsonian courthouse is currently being remodeled into a visitors’ center (bourbon tours!) and the former slave market has been recast as the site of a weekly farmers market. The city’s dining and bar scene is enlivened by two colleges, the University of Kentucky and the tiny, oddly named Transylvania University that, founded in 1780, was the first college west of the Allegheny Mountains.

In 1958, demonstrating considerable foresight, Lexington created an urban growth boundary around the city, so there’s very little suburban sprawl. Leafy residential neighborhoods that ring the downtown quickly give way to horse farms. What’s conspicuously missing, however, is the sort of exalted bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure that has become the hallmark of the 21st-century city. Also MIA: the creek that was Lexington’s original raison d’être.

Which is how I found myself standing with Orff in the parking lot behind the 1976 Lexington Center, an oddly disjointed assemblage of glassy cylinders in front and corrugated concrete in the rear, which incorporates a hotel, shopping mall, convention center, and Rupp Arena, home to the University of Kentucky’s basketball team. The parking lot will eventually be transformed into Town Branch Park, a 10-acre privately funded green space with lawns, performance spaces, and a creek-inspired splash pad—a tantalizing destination for bikers and walkers along the new greenway.

Scape

A rendering of a waterpark near the convention center

Right now, the site is nothing more than a sheet of asphalt facing the sorry underside of the center. The stream runs under the blacktop. “Where you see the drains,” Orff says pointing to a line of sewer grates, “is the Town Branch culvert.” Beyond the edge of the parking lot, which is pretty much the downtown’s western limit, and beyond a metal highway barrier that gives way to an expanse of grass, the waterway itself reappears, a perfectly pleasant little stream.

Town Branch Commons is exactly the sort of undertaking for which Orff is building a reputation. The founder of Scape, and the director of Columbia University’s graduate Urban Design Program, Orff is at the forefront of a movement in which a deep understanding of the natural world informs the design of the manmade one. Scape won the project in a 2013 design competition sponsored by Lexington’s Downtown Development Authority, and construction is scheduled to begin later this year.

The Idea of a City on the Water

About two decades ago, a local architect named Van Meter Pettit, AIA, figured out exactly what Town Branch meant to Lexington. His family happened to own a McKim, Mead & White building downtown (now the 21C Hotel), whose basement required nonstop pumping and that clued him in to the creek’s existence. Familiar with the Delaware and Raritan canal towpath in central New Jersey and Austin, Texas’ Town Lake trails, he could envision the lost stream’s potential. In 1998, Pettit founded an organization called Town Branch Trail, with a mission to “connect the city with its world-famous countryside and reorient the cityscape to its founding along the creek.”

In 2010, Jim Gray, a local contractor, was elected mayor, and he set up a task force to update and improve the convention center area. According to planner Stanford Harvey, a principal at Lord Aeck Sargent and a long-standing participant in the project, the new mayor “saw a waste and an opportunity, that the city owned 46 acres right in the middle of downtown that was mostly surface parking lots.”

Midland Avenue now and after the redesign

The task force hired architect Gary Bates from Oslo, Norway–based Space Group. “Gary got it immediately to an extent that kind of amazed me,” Pettit recalls. “He made Town Branch the centerpiece of his schematic plans.”

As Harvey explains it: “I think there’s two things that resonated. One is this idea of a city on the water, the idea that they thought we somehow are going to bring water back.

“And the second thing is,” Harvey continues, “Lexington is pretty much defined by the horse farms, so this idea of a green ribbon coming through downtown that is somehow about the farms and what Lexington means … people really liked that idea too. Particularly if it’s a trail that connected out to those farms as well.”

“The arena project was shelved,” says Pettit, “but the Town Branch concept was promoted as a stand-alone design competition.”

In the ensuing proposals, most of the firms did the obvious thing, according to Gena Wirth, a design principal at Scape: They daylit the length of Town Branch through downtown, liberating it from its culvert, and made it into a riverwalk, like the one in San Antonio, even though Town Branch is a far less substantial waterway. Scape, on the other hand, immersed itself in the natural environment of the bluegrass region, in particular the way a porous limestone called karst has shaped the local economy and ecology. Apparently, the limestone nourishes the grass, thereby strengthening the bones of the horses that graze on it; it also infuses the bourbon for which the state is famous. And it causes water to behave in unusual ways, which influenced Orff’s design. In her 2016 book, Toward an Urban Ecology, she wrote: “Underground waterways travel through permeable limestone layers and surface into pools, disappear into sinks, and dramatically resurface where least expected. Rather than express Town Branch as a linear channel, the project aims to reveal a karst identity through a network of water windows, pools, pockets, fountains, and filter gardens that evoke and expose the underground stream.”

A diagram of the streetscape now and after the redesign

Scape’s idea is clever: Town Branch Commons will be a linear park squeezed into space created by narrowing the traffic lanes on Vine and repurposing some of downtown’s many surface parking lots. The park will be continuous, but the actual creek will not. Sometimes it will be evoked with pools, stormwater-cleansing filtration gardens, and a variety of other water features. The distinctive karst walls, made from diagonal slabs of stone, common in the surrounding countryside, will be a recurrent motif in the project, used as the inspiration for benches, barriers, and paving patterns.

The Department of Transportation, in awarding Town Branch Commons the grant, saw the project as a “multimodal greenway” and was especially swayed by the idea that the section it was funding would link to 20 additional miles of rural trails. The project’s overall budget, just shy of $40 million, also came from other federal sources, plus city and state transportation and environmental budgets. The two largest park areas are being paid for separately, by private donations. But it was the TIGER grant that made the project feel like a done deal, according to Harvey: “People were taken aback: They actually raised all of the money to do this. This is actually going to happen.”

Mayor Gray discusses Town Branch Commons the way his 1970s predecessor likely spoke of the convention center: “I’m saying it’s essential, essential in the competitive landscape today,” he told me. “Having a compelling, inviting, welcoming urban space through it is a big part of maintaining competitive advantage in an economic sense.”

Gray’s director of project management, Jonathan Hollinger, put it this way: “We see this as 21st-century infrastructure. What we’ve done over the last 50 years is built infrastructure for cars.” No matter how technology changes the city’s future needs, he argues, “I can say with great certainty that we’ll always be able to walk.”

Vine Street now and after the redesign

What Losing TIGER Would Mean

The revitalization of American cities that has occurred over the past decade can be attributed, in part, to the way the federal government has rewarded urban centers that took the needs of their walkers, bicyclists, and transit riders seriously. This hasn’t prevented the Trump administration from targeting TIGER grants in its budget. In theory, the Town Branch project should appeal to politicians on both sides of the aisle. In fact, Lexington officials rallied support for the TIGER grant from Sen. Mitch McConnell (R). When I recently spoke to Shaun Donovan, the former secretary of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, he emphasized that encouraging and funding innovation at a local level should be a bipartisan effort: “In some ways, it’s very consistent with the federalist view of the Republicans that the federal government ought to be a supporter of local communities rather than dictating to local communities.”

Although light on specifics, the Trump administration’s approach to infrastructure appears mainly to be about injecting money into big-ticket projects like highways and airports by privatizing them. There doesn’t seem to be a lot of interest in mass transit and other less carbon-intensive forms of transportation. As Poticha told me: “The message I’m getting from the Trump administration is that they’re only really interested in these big projects that private equity investors can see a return of investment on.”

In other words, this is not an administration that appears intent on embracing the kind of progressive urban thinking that is one of Orff’s strong suits. She describes her approach to incorporating the local ecology into built works as a “revival,” which she defines as “a creative, forward-looking act, not driven by nostalgia for the past.”

Indeed, much of our 21st-century infrastructure has been aimed at repairing the damage done by monumental 20th-century infrastructure. TIGER supports projects that accomplish these aims in a way that isn’t always photogenic or sexy, that may not have the appeal of a cathedral-like airport terminal or a soaring bridge. If Trump’s cuts to TIGER are included in the budget that Congress is slated to pass this fall, what will be lost is a program that prioritizes the layer upon layer of interlocking systems that are frequently unglamorous and boring, and sometimes, like that lost creek in Kentucky, entirely hidden from view.

Back in 2009, it seemed like Obama might champion a nationwide high-speed rail system or a sophisticated new power grid. Ultimately, his administration took a largely piecemeal approach to advancing a progressive urban vision. TIGER encouraged cities like Hartford, Conn.; Akron, Ohio; and Sacramento, Calif., to restore disused train stations, implement bike sharing, and build light-rail or bus rapid transit lines, transforming the country one modest project at a time. “I think the TIGER program has been very successful,” says Shelley Poticha, a former Obama administration official who is now the director of urban solutions for the Natural Resources Defense Council. “It really prioritized investments in local communities and it has empowered [them] to actually use the funds and deliver the projects in a holistic way. It’s probably the only transportation program where the money goes directly to the city.”

Under the new administration, however, TIGER grants may well disappear. The 2018 budget released by the White House in May includes over $16 billion in cuts to the Department of Transportation, and in mid-July, the House passed a spending bill that would eliminate the program. Then, in late July, the Senate Appropriations Committee proposed setting TIGER’S funding at $550 million next year, an increase of $50 million. Will the program survive, or is it destined for a premature death?

Vine Street today and after the redesign

Lexington’s Pedestrian Push

To discover what might be lost, I traveled to Lexington in late June to learn more about Town Branch Commons, which is exactly the kind of quirky, forward-looking project that the TIGER program encourages. During the urban renewal decades, Lexington managed to avoid having an interstate highway rammed through its center, and much of its historic Main Street remains intact. Downtown, a hulking Richardsonian courthouse is currently being remodeled into a visitors’ center (bourbon tours!) and the former slave market has been recast as the site of a weekly farmers market. The city’s dining and bar scene is enlivened by two colleges, the University of Kentucky and the tiny, oddly named Transylvania University that, founded in 1780, was the first college west of the Allegheny Mountains.

In 1958, demonstrating considerable foresight, Lexington created an urban growth boundary around the city, so there’s very little suburban sprawl. Leafy residential neighborhoods that ring the downtown quickly give way to horse farms. What’s conspicuously missing, however, is the sort of exalted bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure that has become the hallmark of the 21st-century city. Also MIA: the creek that was Lexington’s original raison d’être.

Which is how I found myself standing with Orff in the parking lot behind the 1976 Lexington Center, an oddly disjointed assemblage of glassy cylinders in front and corrugated concrete in the rear, which incorporates a hotel, shopping mall, convention center, and Rupp Arena, home to the University of Kentucky’s basketball team. The parking lot will eventually be transformed into Town Branch Park, a 10-acre privately funded green space with lawns, performance spaces, and a creek-inspired splash pad—a tantalizing destination for bikers and walkers along the new greenway.

Scape

A rendering of a waterpark near the convention center

Right now, the site is nothing more than a sheet of asphalt facing the sorry underside of the center. The stream runs under the blacktop. “Where you see the drains,” Orff says pointing to a line of sewer grates, “is the Town Branch culvert.” Beyond the edge of the parking lot, which is pretty much the downtown’s western limit, and beyond a metal highway barrier that gives way to an expanse of grass, the waterway itself reappears, a perfectly pleasant little stream.

Town Branch Commons is exactly the sort of undertaking for which Orff is building a reputation. The founder of Scape, and the director of Columbia University’s graduate Urban Design Program, Orff is at the forefront of a movement in which a deep understanding of the natural world informs the design of the manmade one. Scape won the project in a 2013 design competition sponsored by Lexington’s Downtown Development Authority, and construction is scheduled to begin later this year.

The Idea of a City on the Water

About two decades ago, a local architect named Van Meter Pettit, AIA, figured out exactly what Town Branch meant to Lexington. His family happened to own a McKim, Mead & White building downtown (now the 21C Hotel), whose basement required nonstop pumping and that clued him in to the creek’s existence. Familiar with the Delaware and Raritan canal towpath in central New Jersey and Austin, Texas’ Town Lake trails, he could envision the lost stream’s potential. In 1998, Pettit founded an organization called Town Branch Trail, with a mission to “connect the city with its world-famous countryside and reorient the cityscape to its founding along the creek.”

In 2010, Jim Gray, a local contractor, was elected mayor, and he set up a task force to update and improve the convention center area. According to planner Stanford Harvey, a principal at Lord Aeck Sargent and a long-standing participant in the project, the new mayor “saw a waste and an opportunity, that the city owned 46 acres right in the middle of downtown that was mostly surface parking lots.”

Midland Avenue now and after the redesign

The task force hired architect Gary Bates from Oslo, Norway–based Space Group. “Gary got it immediately to an extent that kind of amazed me,” Pettit recalls. “He made Town Branch the centerpiece of his schematic plans.”

As Harvey explains it: “I think there’s two things that resonated. One is this idea of a city on the water, the idea that they thought we somehow are going to bring water back.

“And the second thing is,” Harvey continues, “Lexington is pretty much defined by the horse farms, so this idea of a green ribbon coming through downtown that is somehow about the farms and what Lexington means … people really liked that idea too. Particularly if it’s a trail that connected out to those farms as well.”

“The arena project was shelved,” says Pettit, “but the Town Branch concept was promoted as a stand-alone design competition.”

In the ensuing proposals, most of the firms did the obvious thing, according to Gena Wirth, a design principal at Scape: They daylit the length of Town Branch through downtown, liberating it from its culvert, and made it into a riverwalk, like the one in San Antonio, even though Town Branch is a far less substantial waterway. Scape, on the other hand, immersed itself in the natural environment of the bluegrass region, in particular the way a porous limestone called karst has shaped the local economy and ecology. Apparently, the limestone nourishes the grass, thereby strengthening the bones of the horses that graze on it; it also infuses the bourbon for which the state is famous. And it causes water to behave in unusual ways, which influenced Orff’s design. In her 2016 book, Toward an Urban Ecology, she wrote: “Underground waterways travel through permeable limestone layers and surface into pools, disappear into sinks, and dramatically resurface where least expected. Rather than express Town Branch as a linear channel, the project aims to reveal a karst identity through a network of water windows, pools, pockets, fountains, and filter gardens that evoke and expose the underground stream.”

A diagram of the streetscape now and after the redesign

Scape’s idea is clever: Town Branch Commons will be a linear park squeezed into space created by narrowing the traffic lanes on Vine and repurposing some of downtown’s many surface parking lots. The park will be continuous, but the actual creek will not. Sometimes it will be evoked with pools, stormwater-cleansing filtration gardens, and a variety of other water features. The distinctive karst walls, made from diagonal slabs of stone, common in the surrounding countryside, will be a recurrent motif in the project, used as the inspiration for benches, barriers, and paving patterns.

The Department of Transportation, in awarding Town Branch Commons the grant, saw the project as a “multimodal greenway” and was especially swayed by the idea that the section it was funding would link to 20 additional miles of rural trails. The project’s overall budget, just shy of $40 million, also came from other federal sources, plus city and state transportation and environmental budgets. The two largest park areas are being paid for separately, by private donations. But it was the TIGER grant that made the project feel like a done deal, according to Harvey: “People were taken aback: They actually raised all of the money to do this. This is actually going to happen.”

Mayor Gray discusses Town Branch Commons the way his 1970s predecessor likely spoke of the convention center: “I’m saying it’s essential, essential in the competitive landscape today,” he told me. “Having a compelling, inviting, welcoming urban space through it is a big part of maintaining competitive advantage in an economic sense.”

Gray’s director of project management, Jonathan Hollinger, put it this way: “We see this as 21st-century infrastructure. What we’ve done over the last 50 years is built infrastructure for cars.” No matter how technology changes the city’s future needs, he argues, “I can say with great certainty that we’ll always be able to walk.”

Vine Street now and after the redesign

What Losing TIGER Would Mean

The revitalization of American cities that has occurred over the past decade can be attributed, in part, to the way the federal government has rewarded urban centers that took the needs of their walkers, bicyclists, and transit riders seriously. This hasn’t prevented the Trump administration from targeting TIGER grants in its budget. In theory, the Town Branch project should appeal to politicians on both sides of the aisle. In fact, Lexington officials rallied support for the TIGER grant from Sen. Mitch McConnell (R). When I recently spoke to Shaun Donovan, the former secretary of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, he emphasized that encouraging and funding innovation at a local level should be a bipartisan effort: “In some ways, it’s very consistent with the federalist view of the Republicans that the federal government ought to be a supporter of local communities rather than dictating to local communities.”

Although light on specifics, the Trump administration’s approach to infrastructure appears mainly to be about injecting money into big-ticket projects like highways and airports by privatizing them. There doesn’t seem to be a lot of interest in mass transit and other less carbon-intensive forms of transportation. As Poticha told me: “The message I’m getting from the Trump administration is that they’re only really interested in these big projects that private equity investors can see a return of investment on.”

In other words, this is not an administration that appears intent on embracing the kind of progressive urban thinking that is one of Orff’s strong suits. She describes her approach to incorporating the local ecology into built works as a “revival,” which she defines as “a creative, forward-looking act, not driven by nostalgia for the past.”

Indeed, much of our 21st-century infrastructure has been aimed at repairing the damage done by monumental 20th-century infrastructure. TIGER supports projects that accomplish these aims in a way that isn’t always photogenic or sexy, that may not have the appeal of a cathedral-like airport terminal or a soaring bridge. If Trump’s cuts to TIGER are included in the budget that Congress is slated to pass this fall, what will be lost is a program that prioritizes the layer upon layer of interlocking systems that are frequently unglamorous and boring, and sometimes, like that lost creek in Kentucky, entirely hidden from view.

Back in 2009, it seemed like Obama might champion a nationwide high-speed rail system or a sophisticated new power grid. Ultimately, his administration took a largely piecemeal approach to advancing a progressive urban vision. TIGER encouraged cities like Hartford, Conn.; Akron, Ohio; and Sacramento, Calif., to restore disused train stations, implement bike sharing, and build light-rail or bus rapid transit lines, transforming the country one modest project at a time. “I think the TIGER program has been very successful,” says Shelley Poticha, a former Obama administration official who is now the director of urban solutions for the Natural Resources Defense Council. “It really prioritized investments in local communities and it has empowered [them] to actually use the funds and deliver the projects in a holistic way. It’s probably the only transportation program where the money goes directly to the city.”

Under the new administration, however, TIGER grants may well disappear. The 2018 budget released by the White House in May includes over $16 billion in cuts to the Department of Transportation, and in mid-July, the House passed a spending bill that would eliminate the program. Then, in late July, the Senate Appropriations Committee proposed setting TIGER’S funding at $550 million next year, an increase of $50 million. Will the program survive, or is it destined for a premature death?

Vine Street today and after the redesign

Lexington’s Pedestrian Push

To discover what might be lost, I traveled to Lexington in late June to learn more about Town Branch Commons, which is exactly the kind of quirky, forward-looking project that the TIGER program encourages. During the urban renewal decades, Lexington managed to avoid having an interstate highway rammed through its center, and much of its historic Main Street remains intact. Downtown, a hulking Richardsonian courthouse is currently being remodeled into a visitors’ center (bourbon tours!) and the former slave market has been recast as the site of a weekly farmers market. The city’s dining and bar scene is enlivened by two colleges, the University of Kentucky and the tiny, oddly named Transylvania University that, founded in 1780, was the first college west of the Allegheny Mountains.

In 1958, demonstrating considerable foresight, Lexington created an urban growth boundary around the city, so there’s very little suburban sprawl. Leafy residential neighborhoods that ring the downtown quickly give way to horse farms. What’s conspicuously missing, however, is the sort of exalted bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure that has become the hallmark of the 21st-century city. Also MIA: the creek that was Lexington’s original raison d’être.

Which is how I found myself standing with Orff in the parking lot behind the 1976 Lexington Center, an oddly disjointed assemblage of glassy cylinders in front and corrugated concrete in the rear, which incorporates a hotel, shopping mall, convention center, and Rupp Arena, home to the University of Kentucky’s basketball team. The parking lot will eventually be transformed into Town Branch Park, a 10-acre privately funded green space with lawns, performance spaces, and a creek-inspired splash pad—a tantalizing destination for bikers and walkers along the new greenway.

Scape

A rendering of a waterpark near the convention center

Right now, the site is nothing more than a sheet of asphalt facing the sorry underside of the center. The stream runs under the blacktop. “Where you see the drains,” Orff says pointing to a line of sewer grates, “is the Town Branch culvert.” Beyond the edge of the parking lot, which is pretty much the downtown’s western limit, and beyond a metal highway barrier that gives way to an expanse of grass, the waterway itself reappears, a perfectly pleasant little stream.

Town Branch Commons is exactly the sort of undertaking for which Orff is building a reputation. The founder of Scape, and the director of Columbia University’s graduate Urban Design Program, Orff is at the forefront of a movement in which a deep understanding of the natural world informs the design of the manmade one. Scape won the project in a 2013 design competition sponsored by Lexington’s Downtown Development Authority, and construction is scheduled to begin later this year.

The Idea of a City on the Water

About two decades ago, a local architect named Van Meter Pettit, AIA, figured out exactly what Town Branch meant to Lexington. His family happened to own a McKim, Mead & White building downtown (now the 21C Hotel), whose basement required nonstop pumping and that clued him in to the creek’s existence. Familiar with the Delaware and Raritan canal towpath in central New Jersey and Austin, Texas’ Town Lake trails, he could envision the lost stream’s potential. In 1998, Pettit founded an organization called Town Branch Trail, with a mission to “connect the city with its world-famous countryside and reorient the cityscape to its founding along the creek.”

In 2010, Jim Gray, a local contractor, was elected mayor, and he set up a task force to update and improve the convention center area. According to planner Stanford Harvey, a principal at Lord Aeck Sargent and a long-standing participant in the project, the new mayor “saw a waste and an opportunity, that the city owned 46 acres right in the middle of downtown that was mostly surface parking lots.”

Midland Avenue now and after the redesign

The task force hired architect Gary Bates from Oslo, Norway–based Space Group. “Gary got it immediately to an extent that kind of amazed me,” Pettit recalls. “He made Town Branch the centerpiece of his schematic plans.”

As Harvey explains it: “I think there’s two things that resonated. One is this idea of a city on the water, the idea that they thought we somehow are going to bring water back.

“And the second thing is,” Harvey continues, “Lexington is pretty much defined by the horse farms, so this idea of a green ribbon coming through downtown that is somehow about the farms and what Lexington means … people really liked that idea too. Particularly if it’s a trail that connected out to those farms as well.”

“The arena project was shelved,” says Pettit, “but the Town Branch concept was promoted as a stand-alone design competition.”

In the ensuing proposals, most of the firms did the obvious thing, according to Gena Wirth, a design principal at Scape: They daylit the length of Town Branch through downtown, liberating it from its culvert, and made it into a riverwalk, like the one in San Antonio, even though Town Branch is a far less substantial waterway. Scape, on the other hand, immersed itself in the natural environment of the bluegrass region, in particular the way a porous limestone called karst has shaped the local economy and ecology. Apparently, the limestone nourishes the grass, thereby strengthening the bones of the horses that graze on it; it also infuses the bourbon for which the state is famous. And it causes water to behave in unusual ways, which influenced Orff’s design. In her 2016 book, Toward an Urban Ecology, she wrote: “Underground waterways travel through permeable limestone layers and surface into pools, disappear into sinks, and dramatically resurface where least expected. Rather than express Town Branch as a linear channel, the project aims to reveal a karst identity through a network of water windows, pools, pockets, fountains, and filter gardens that evoke and expose the underground stream.”

A diagram of the streetscape now and after the redesign

Scape’s idea is clever: Town Branch Commons will be a linear park squeezed into space created by narrowing the traffic lanes on Vine and repurposing some of downtown’s many surface parking lots. The park will be continuous, but the actual creek will not. Sometimes it will be evoked with pools, stormwater-cleansing filtration gardens, and a variety of other water features. The distinctive karst walls, made from diagonal slabs of stone, common in the surrounding countryside, will be a recurrent motif in the project, used as the inspiration for benches, barriers, and paving patterns.

The Department of Transportation, in awarding Town Branch Commons the grant, saw the project as a “multimodal greenway” and was especially swayed by the idea that the section it was funding would link to 20 additional miles of rural trails. The project’s overall budget, just shy of $40 million, also came from other federal sources, plus city and state transportation and environmental budgets. The two largest park areas are being paid for separately, by private donations. But it was the TIGER grant that made the project feel like a done deal, according to Harvey: “People were taken aback: They actually raised all of the money to do this. This is actually going to happen.”

Mayor Gray discusses Town Branch Commons the way his 1970s predecessor likely spoke of the convention center: “I’m saying it’s essential, essential in the competitive landscape today,” he told me. “Having a compelling, inviting, welcoming urban space through it is a big part of maintaining competitive advantage in an economic sense.”

Gray’s director of project management, Jonathan Hollinger, put it this way: “We see this as 21st-century infrastructure. What we’ve done over the last 50 years is built infrastructure for cars.” No matter how technology changes the city’s future needs, he argues, “I can say with great certainty that we’ll always be able to walk.”

Vine Street now and after the redesign

What Losing TIGER Would Mean

The revitalization of American cities that has occurred over the past decade can be attributed, in part, to the way the federal government has rewarded urban centers that took the needs of their walkers, bicyclists, and transit riders seriously. This hasn’t prevented the Trump administration from targeting TIGER grants in its budget. In theory, the Town Branch project should appeal to politicians on both sides of the aisle. In fact, Lexington officials rallied support for the TIGER grant from Sen. Mitch McConnell (R). When I recently spoke to Shaun Donovan, the former secretary of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, he emphasized that encouraging and funding innovation at a local level should be a bipartisan effort: “In some ways, it’s very consistent with the federalist view of the Republicans that the federal government ought to be a supporter of local communities rather than dictating to local communities.”

Although light on specifics, the Trump administration’s approach to infrastructure appears mainly to be about injecting money into big-ticket projects like highways and airports by privatizing them. There doesn’t seem to be a lot of interest in mass transit and other less carbon-intensive forms of transportation. As Poticha told me: “The message I’m getting from the Trump administration is that they’re only really interested in these big projects that private equity investors can see a return of investment on.”

In other words, this is not an administration that appears intent on embracing the kind of progressive urban thinking that is one of Orff’s strong suits. She describes her approach to incorporating the local ecology into built works as a “revival,” which she defines as “a creative, forward-looking act, not driven by nostalgia for the past.”

Indeed, much of our 21st-century infrastructure has been aimed at repairing the damage done by monumental 20th-century infrastructure. TIGER supports projects that accomplish these aims in a way that isn’t always photogenic or sexy, that may not have the appeal of a cathedral-like airport terminal or a soaring bridge. If Trump’s cuts to TIGER are included in the budget that Congress is slated to pass this fall, what will be lost is a program that prioritizes the layer upon layer of interlocking systems that are frequently unglamorous and boring, and sometimes, like that lost creek in Kentucky, entirely hidden from view.